Blueprints: How We Teach Agents to Work the Way Data Engineers Do

I’m Justin Langseth, CTO at Genesis, and I’ve spent most of my career building data systems — from large-scale analytics platforms to AI agents that can actually reason about data.

Over the past 2 years, my team and I have been working on what we call data agents: autonomous systems that can build, fix, and extend data pipelines on their own.

From the outside, that sounds simple — connect an LLM to a few APIs and let it run. But the hard problems appear once you try to make those agents operate for hours, stay coherent, and integrate with real enterprise stacks.

The issues we’ve faced — context overload, tool sprawl, forgotten state — are universal to anyone working with agentic AI.

I started writing this series to show what happens behind the scenes: how we structure agent workflows through blueprints, manage their memory so they can think clearly, and regulate tool use so they don’t drown in complexity. These are lessons learned the hard way, and I’m sharing them because every data engineering team will face the same obstacles eventually — we just happened to get there first.

This is the first post in a three-part series about how we’re making agentic systems actually work at Genesis. The next two will cover Context Management and Progressive Tool Use. But none of that makes sense until you understand what a Blueprint is.

When people first see a data agent run, the first reaction is, “Wow, it can code.” That’s true, but it can also code the wrong thing, very confidently.

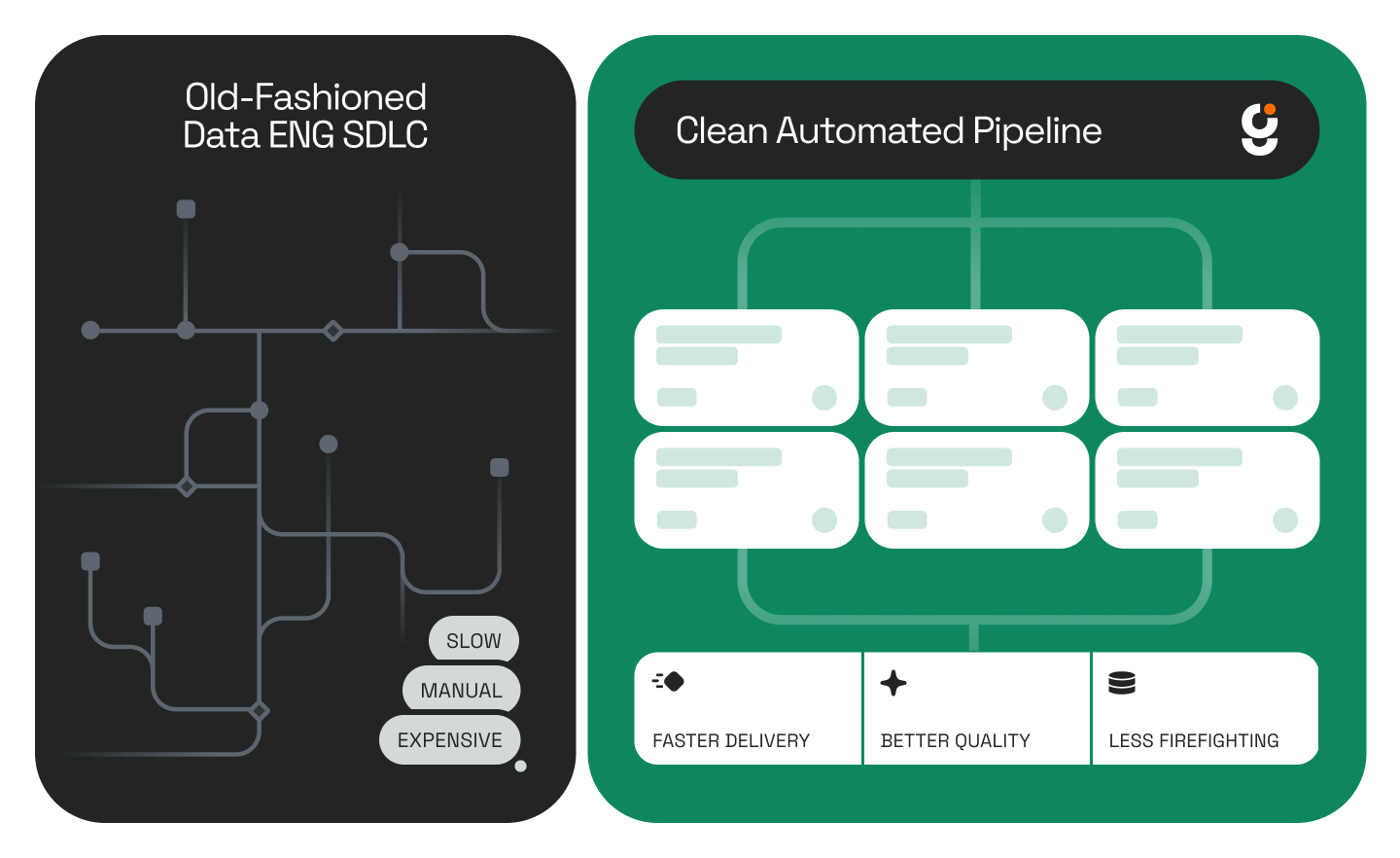

Ask a model to build a reporting table and it will give you something plausible. The problem is, it doesn’t know how the work gets done. It doesn’t understand the order of operations, where ambiguity hides, when to pause, or when to check with a human.

Experienced data engineers do all that instinctively. They follow a quiet, repeatable process. So our question became: how do we give an agent that same sense of procedure?

A Blueprint is our answer. It’s not a prompt template or script; it’s a living methodology that tells an agent how to move through a multi-stage task.

Think of it like the binder every data team wishes they had: When someone asks for a new dashboard, here’s how we handle it. Step 1 — clarify the metric. Step 2 — look for candidate tables. Step 3 — check lineage. Step 4 — get sign-off before coding.

Except in our case, the binder isn’t for people — it’s for agents. The Blueprint sits behind the agent’s reasoning loop and defines what happens at each phase — what information it needs, which tools are relevant, what questions to ask, and what triggers a pause.

Let’s take something every data team does and every LLM struggles with — building a sales report.

A human data engineer hears “sales” and immediately starts unpacking it. Does this mean gross? Net? Adjusted? Is it by order date or invoice date? They know there are probably a dozen candidate tables across Snowflake, Databricks, maybe some legacy warehouse, all shaped a little differently.

A model doesn’t know any of that. It grabs the first thing called sales_data and starts writing SQL.

.png)

In our Field Mapping Blueprint, the agent follows a defined flow that mirrors how engineers actually think:

- Clarify the request. Identify every ambiguous term and restate the goal in plain language.

- Search for candidate sources. Use metadata, lineage, and naming conventions to surface possible tables and fields.

- Evaluate ambiguity. When multiple matches exist, summarize them — don’t decide yet.

- Pause for feedback. Generate concise, directed questions for two audiences:

- Business users: “When you say ‘sales,’ do you mean booked or invoiced?”

- Data owners: “Between these three tables, which one is authoritative?”

- Business users: “When you say ‘sales,’ do you mean booked or invoiced?”

- Update the plan. Integrate the answers, document the reasoning, and store it in Markdown for traceability.

- Generate the code. Translate the confirmed mapping into DBT, Snowpark, or Databricks logic.

At any step, the agent can stop and wait for humans — minutes or days — before continuing. That’s deliberate. It’s the digital version of a mid-level engineer walking over to someone’s desk to double-check before building the wrong thing.

Each Blueprint covers one repeatable process — mapping, pipeline build, failure analysis, QA. When we deliver them, they work out of the box. But the real value starts once a customer runs them a few times.

We call this the safety-driving phase. The agent runs the Blueprint while a human watches and occasionally grabs the wheel — adding notes, clarifying edge cases, maybe rewriting a step or two. After a few drives, the agent has captured enough local knowledge to fork the Blueprint into that company’s own version.

That fork becomes a living artifact: the company’s data-engineering methodology rendered in code and versioned in Git. It’s their intellectual property now — the way they build things, distilled into a repeatable sequence both humans and agents can follow.

Agents are powerful but forgetful. They lose context fast. Blueprints provide the skeleton the rest of the system hangs on. Context Management (which I’ll talk about next) keeps their memory clean; Blueprints tell them what to remember and when it matters.

Without structure, you get speed without reliability. With it, you get a system that behaves like a mid-level engineer — cautious, methodical, aware of what it doesn’t know.

That’s the goal. Not to replace data teams, but to encode their judgment so every run, every agent, and every project gets a little smarter.

Keep Reading

Stay Connected!

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%201%20(1).jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

%201%20(1).jpg)