Progressive Tool Use

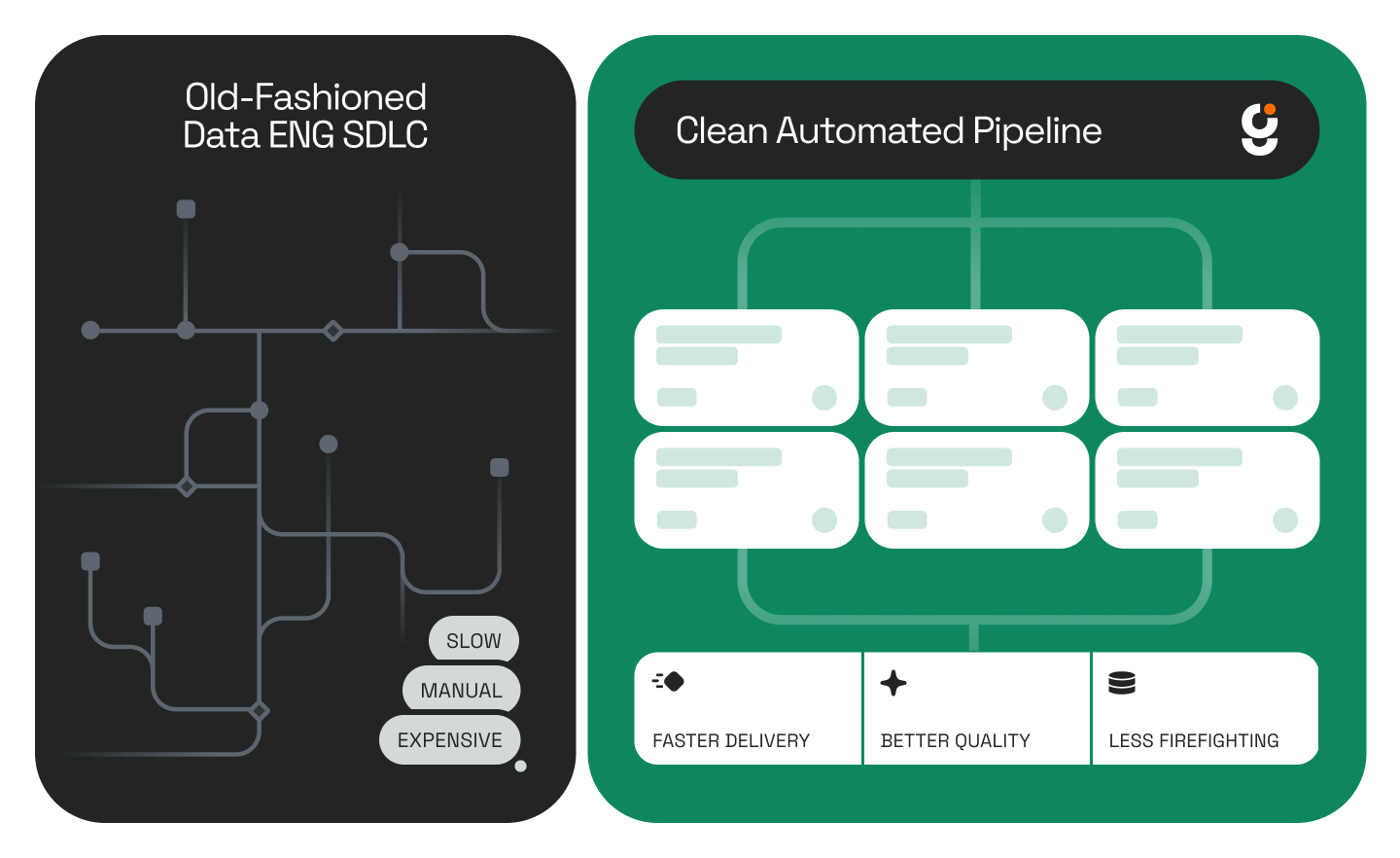

In Part 1 – Blueprints, I explained how agents follow structured workflows instead of improvising. In Part 2 – Context Management, I talked about how they keep their heads clear across hundreds of steps. This last part is about the execution layer — how agents decide which tools to bring into scope at each stage of a data workflow, and how to keep reasoning stable as the environment grows.

Anyone who’s managed complex data pipelines knows what happens when everything connects to everything else. You end up with overlapping jobs, half-deprecated connectors, and a DAG that only works if nobody touches it. Large tool inventories cause the same chaos inside an agent’s head. Every SQL client, catalog API, schema parser, and validation script expands the model’s internal vocabulary. Even when half of them aren’t needed, the model still carries the mental weight of choosing among them. The result is the same kind of backpressure you see when too many upstream jobs push into the same sink — performance drops, accuracy slips, and debugging turns into archaeology.

Tool orchestration in agent systems feels a lot like data plumbing. Each tool is a valve or a section of pipe that handles a specific part of the flow. If you open every valve at once, pressure drops and data backs up. Progressive tool use is about keeping that flow regulated.

.png)

The agent activates only the tools needed for the current stage of the blueprint, closes them when finished, and moves downstream with a clean workspace. It’s controlled throughput instead of all-or-nothing concurrency.

When one stage produces an output that becomes the input for the next, the agent links those tools directly. A metadata extraction might feed a schema inference step, which then passes its output to a validation layer. That linkage happens dynamically, so the tools stay in scope only as long as they’re relevant. If the agent encounters a missing capability — say, a lineage tracer it can’t find — it flags the gap instead of stalling. We log those requests, review them later, and decide whether the new connector belongs in the standard environment. That way, the system grows based on real use, not theoretical coverage.

Every active tool also adds cost: state to maintain, query context to remember, and latency that compounds across long chains of calls. When the agent finishes a section of work, it drops that state and releases the connectors. That automatic cleanup keeps long-running blueprints deterministic. We’ve seen what happens when cleanup is skipped — metrics drift, transformations desynchronize, and the whole run becomes non-reproducible. So cleanup isn’t optional; it’s part of the discipline, just like versioning or lineage tracking.

We’re still learning what “too many tools” means. It depends on the model family, the schema size, and how verbose the tools are. So far it seems safer to start minimal — expose only what’s required — and let the system request expansions as it proves it needs them. That pattern mirrors good data engineering: maintain flow control, reduce width, and prevent context pollution at every stage.

When tools, context, and blueprints align, the agent starts behaving like a disciplined data engineer. It knows which table it’s touching, which lineage it belongs to, and which downstream step depends on its output. That’s when automation stops feeling like orchestration and starts looking like real operational intelligence — a system that understands, executes, and maintains the integrity of data flow at scale.

.png)

.png)

.png)